Last Tuesday, I was able to attend the Joint Committee on Education's hearing in Boston. I say "able" because, while I am sure the legislation before the Committee would have garnered interest and testimony from many active educators, they largely would not have been able to attend as the hearing took place the day after Labor Day, a school day. As a teacher retiree, I was not in my first (or fourth) day of a new school year and could attend, so I did.There were many proposed pieces of legislation under discussion last Tuesday; however, two bills, S.279 and H.304, aroused my curiosity and alarm. These two pieces of legislation appear to target teachers and students in gateway cities and, if you are a Massachusetts parent, teacher, or administrator and your student attends school in one of these districts, you should pay attention. Your voice in what happens in your local school is being threatened.Bill, S. 279 unnecessarily singles out and targets urban and gateway districts. How do I know this? Because the "opportunity" to become an innovation partnership zone is based on a the results of a single high-stakes test, the MCAS and consequently the assigned school level that stems from that test. To base the worth or value of a school - or a district - on how students perform on a single high-stakes exam is w.r.o.n.g. It is bad educational practice. No teacher would ever give a student a final mark based on one measure and the Commonwealth shouldn't be doing this with schools and school districts either.Those who favored moving H.304 and S.279 forward spoke frequently about the power of looking at students' (test) results and collaborating to determine school budget priorities, schedule/time allocations, and coordination of student needs with curriculum. My reaction to that is NO KIDDING. Why, why, why, do some in the Commonwealth feel that a piece of Legislation would make this a) any different from current practice, or b) necessary to mandate?Those in favor also spoke about the empowerment zone created in Springfield. The Springfield schools working in the empowerment zone are all middle schools and have done so for two years. Even James Peyser, Secretary of Education, had to admit the "data" on the success of these schools was rather green and not established. Others from this panel (two teachers and a principal) spoke about their experience meeting as teacher teams to think about what the students need.Sorry kids this is not a new concept or practice, nor is it one that requires a mandate from the Commonwealth. Lowell teachers, and I suspect teachers in most districts throughout Massachusetts, routinely meet to do this very same thing regularly. We call these collaborations PLCs (professional learning communities) or CPTs (common planning time). We do these things because a) we are there to figure out how to help students go from learning point A to B and b) we are professionals.Here's another thought: if a school is considered lower performing according to MCAS results, H.304 and S.279 would allow the Commissioner of Education (appointed, not elected) to begin the process of designating the schools for empowerment or innovation zone status. In the case of H.304, if the local teachers' union and the school committee cannot agree to concessions to the collective bargaining agreement, the Commissioner can just make the school a lower Level 4, and in effect, start the process of diluting local control anyway.Under S.279, the legislations proposes to "support" struggling schools through the creation of an innovation partnership zone. From what I can tell, the "partnership" is that the Commissioner of Education and DESE has a large stake in how the school is run. Schools are eligible to be in an innovation zone if their MCAS scores put them in Level 4 or Level 5 status. But - and this is key - in order to create an innovation zone, there needs to be at least 2 schools participating.Just to put that into local perspective, if Lowell has a Level 4 school (and it does) and the decision was made to create an innovation partnership zone for that school, the Commissioner of Education could pair that Level 4 school with another higher performing school - a Level 3, a Level 2 or a Level 1. So don't breathe easy if your school's MCAS results are great, you too could be part of this education magic show.When a school is "in the zone" (sorry Vygotsky fans, I couldn't resist that), an appointed

Last Tuesday, I was able to attend the Joint Committee on Education's hearing in Boston. I say "able" because, while I am sure the legislation before the Committee would have garnered interest and testimony from many active educators, they largely would not have been able to attend as the hearing took place the day after Labor Day, a school day. As a teacher retiree, I was not in my first (or fourth) day of a new school year and could attend, so I did.There were many proposed pieces of legislation under discussion last Tuesday; however, two bills, S.279 and H.304, aroused my curiosity and alarm. These two pieces of legislation appear to target teachers and students in gateway cities and, if you are a Massachusetts parent, teacher, or administrator and your student attends school in one of these districts, you should pay attention. Your voice in what happens in your local school is being threatened.Bill, S. 279 unnecessarily singles out and targets urban and gateway districts. How do I know this? Because the "opportunity" to become an innovation partnership zone is based on a the results of a single high-stakes test, the MCAS and consequently the assigned school level that stems from that test. To base the worth or value of a school - or a district - on how students perform on a single high-stakes exam is w.r.o.n.g. It is bad educational practice. No teacher would ever give a student a final mark based on one measure and the Commonwealth shouldn't be doing this with schools and school districts either.Those who favored moving H.304 and S.279 forward spoke frequently about the power of looking at students' (test) results and collaborating to determine school budget priorities, schedule/time allocations, and coordination of student needs with curriculum. My reaction to that is NO KIDDING. Why, why, why, do some in the Commonwealth feel that a piece of Legislation would make this a) any different from current practice, or b) necessary to mandate?Those in favor also spoke about the empowerment zone created in Springfield. The Springfield schools working in the empowerment zone are all middle schools and have done so for two years. Even James Peyser, Secretary of Education, had to admit the "data" on the success of these schools was rather green and not established. Others from this panel (two teachers and a principal) spoke about their experience meeting as teacher teams to think about what the students need.Sorry kids this is not a new concept or practice, nor is it one that requires a mandate from the Commonwealth. Lowell teachers, and I suspect teachers in most districts throughout Massachusetts, routinely meet to do this very same thing regularly. We call these collaborations PLCs (professional learning communities) or CPTs (common planning time). We do these things because a) we are there to figure out how to help students go from learning point A to B and b) we are professionals.Here's another thought: if a school is considered lower performing according to MCAS results, H.304 and S.279 would allow the Commissioner of Education (appointed, not elected) to begin the process of designating the schools for empowerment or innovation zone status. In the case of H.304, if the local teachers' union and the school committee cannot agree to concessions to the collective bargaining agreement, the Commissioner can just make the school a lower Level 4, and in effect, start the process of diluting local control anyway.Under S.279, the legislations proposes to "support" struggling schools through the creation of an innovation partnership zone. From what I can tell, the "partnership" is that the Commissioner of Education and DESE has a large stake in how the school is run. Schools are eligible to be in an innovation zone if their MCAS scores put them in Level 4 or Level 5 status. But - and this is key - in order to create an innovation zone, there needs to be at least 2 schools participating.Just to put that into local perspective, if Lowell has a Level 4 school (and it does) and the decision was made to create an innovation partnership zone for that school, the Commissioner of Education could pair that Level 4 school with another higher performing school - a Level 3, a Level 2 or a Level 1. So don't breathe easy if your school's MCAS results are great, you too could be part of this education magic show.When a school is "in the zone" (sorry Vygotsky fans, I couldn't resist that), an appointed  Board of Directors has autonomous control over personnel, budget, curriculum and hours. This unelected board with possibly no connection to the community could decide to do anything, including conversion of the public school to a charter school through a charter management company.Just for comparison, if a school is not in the zone, the elected School Committee and a combination of school administration/school site councils (theoretically) make these decisions and if you, a parent or voter, don't agree with those decisions, you can voice that in person or you can make your feelings known at the ballot box.Wait. Who is missing from those groups? If you said "teachers", you go right to the bullseye of the Zone of Proximal Development. At least on this topic. Despite the Springfield testimony highlighting empowering teachers and teacher teams, the decision-making for what takes place in a classroom is still top-down.The act of creating empowerment or innovation zones is different from what has happened in a few districts in Massachusetts, namely Lawrence. In those districts the state has outright put the entire district into receivership, meaning, the local governance of the public schools is given over to the Commonwealth. There is no local control over the education of the students and an un-elected "receiver" makes all the decisions. It also includes a favorable environment for education management organizations (EMO) to set up a network of charter schools. If you are interested in the track record of the charter school industry in Michigan and in particular Detroit where entire public school districts were replaced by charter school entities, read this article from the NY Times. Chilling.The full text of S.279 is found here, and the full text of H.304 is found here. For now, both of these bills warrant a close watch. The Department of Elementary and Secondary Education seem to be ready to dismantle traditional public education one school at a time.

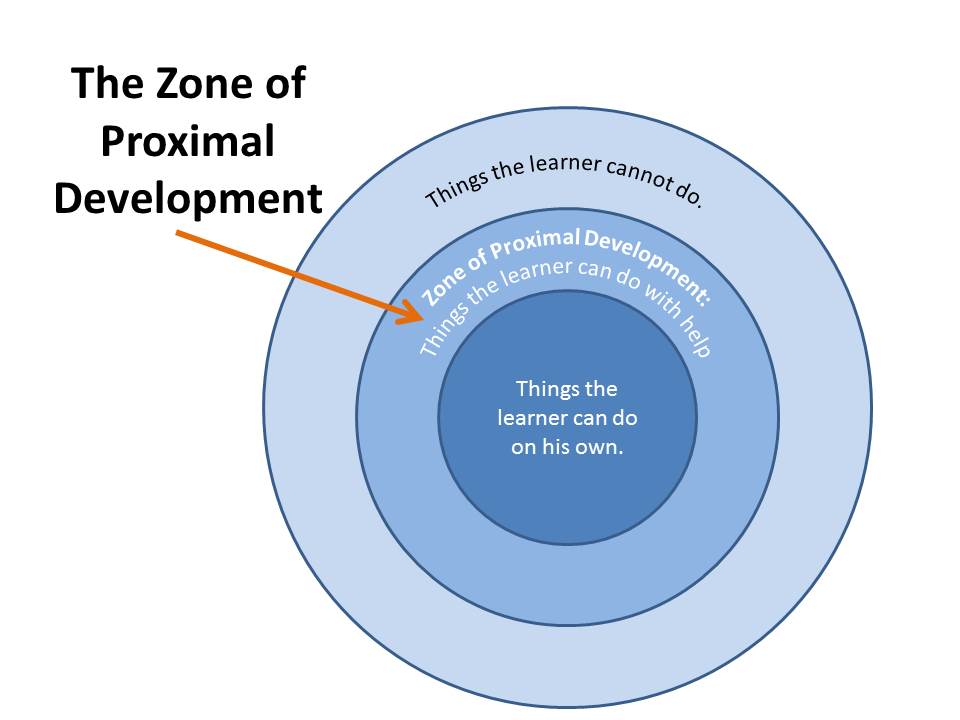

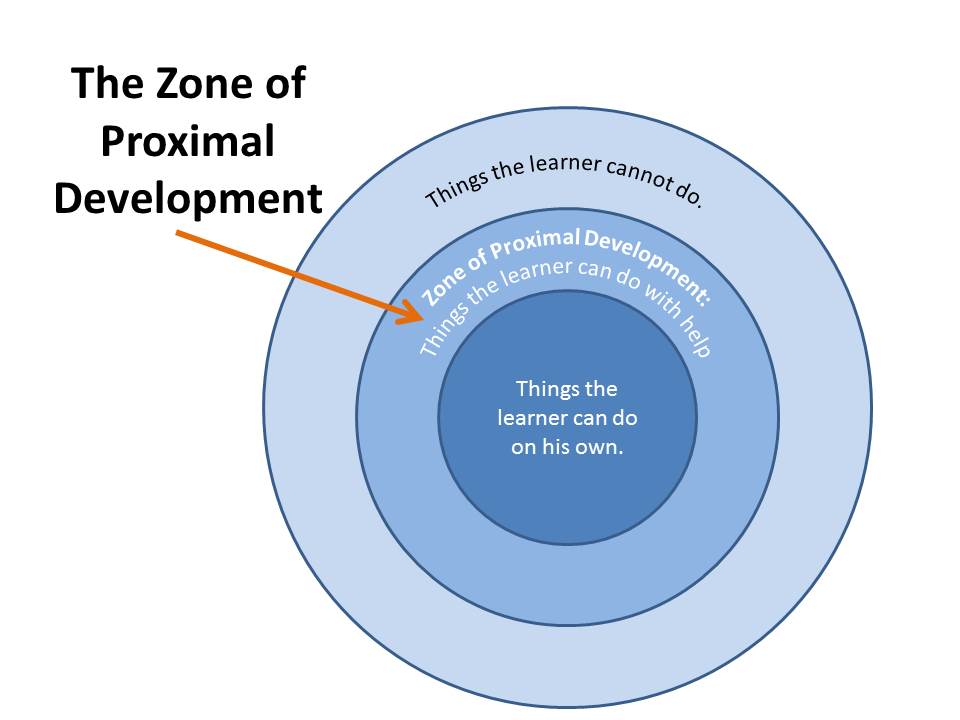

Board of Directors has autonomous control over personnel, budget, curriculum and hours. This unelected board with possibly no connection to the community could decide to do anything, including conversion of the public school to a charter school through a charter management company.Just for comparison, if a school is not in the zone, the elected School Committee and a combination of school administration/school site councils (theoretically) make these decisions and if you, a parent or voter, don't agree with those decisions, you can voice that in person or you can make your feelings known at the ballot box.Wait. Who is missing from those groups? If you said "teachers", you go right to the bullseye of the Zone of Proximal Development. At least on this topic. Despite the Springfield testimony highlighting empowering teachers and teacher teams, the decision-making for what takes place in a classroom is still top-down.The act of creating empowerment or innovation zones is different from what has happened in a few districts in Massachusetts, namely Lawrence. In those districts the state has outright put the entire district into receivership, meaning, the local governance of the public schools is given over to the Commonwealth. There is no local control over the education of the students and an un-elected "receiver" makes all the decisions. It also includes a favorable environment for education management organizations (EMO) to set up a network of charter schools. If you are interested in the track record of the charter school industry in Michigan and in particular Detroit where entire public school districts were replaced by charter school entities, read this article from the NY Times. Chilling.The full text of S.279 is found here, and the full text of H.304 is found here. For now, both of these bills warrant a close watch. The Department of Elementary and Secondary Education seem to be ready to dismantle traditional public education one school at a time.

What will it take to break through the glass ceiling of education leadership in Massachusetts? The answer to that is still to be uncovered.On Monday, the Board of Education met to make a final candidate selection for Massachusetts' next Commissioner of Education. There were three candidates: Penny Schwinn, Angelica Infante-Green, and Jeffrey Riley. Two of the candidates, both women, were from "out-of-state"; Mr. Riley is a known quantity who has most recently been the Receiver of the Lawrence Public Schools.One would think that with two women in the final three, there would be a fairly decent chance that the next Commissioner might be a woman, but that would mean ignoring what seems to be an unspoken qualification for education commissioner: "known local quantity". Mr. Riley currently holds the position of Receiver in Lawrence Public Schools and has since that city's schools were put under state receivership. He recently resigned the Receiver's position and one wonders if that were serendipitous or by design.By many accounts, Ms. Infante-Green's interview was quite remarkable; she is a strong advocate of both bilingual and special education. As a parent of two bilingual children, one diagnosed with autism, she understands these two important issues intimately. While I disagree with some of her positions, she would have been a formidable advocate for bilingual students and for the differently-abled. To my thinking, the BESE members' failure to select her as Masachusetts' next Commissioner of Education is a lost opportunity: the opportunity to select the first woman to head the Commonwealth's Department of Elementary and Secondary Education and the first Latina to head Massachusetts' education.From each board members commentary, I think many of them supported Ms. Infante-Green's candidacy, but could not, in the end make that selection. It felt as if many of the eight who selected Mr. Riley did so based on a perception of "earning" the position after his tenure in Lawrence. It was safer. So what we seem to have here is a safe, unimaginative selection; hopefully I will be proven incorrect about that last part.Instead of breaking that glass ceiling, Massachusetts' Board of Elementary and Secondary Education chose the safe, known, local candidate. In doing so, have state policy-makers missed an opportunity for greatness? I believe so. Missed opportunity indeed.

What will it take to break through the glass ceiling of education leadership in Massachusetts? The answer to that is still to be uncovered.On Monday, the Board of Education met to make a final candidate selection for Massachusetts' next Commissioner of Education. There were three candidates: Penny Schwinn, Angelica Infante-Green, and Jeffrey Riley. Two of the candidates, both women, were from "out-of-state"; Mr. Riley is a known quantity who has most recently been the Receiver of the Lawrence Public Schools.One would think that with two women in the final three, there would be a fairly decent chance that the next Commissioner might be a woman, but that would mean ignoring what seems to be an unspoken qualification for education commissioner: "known local quantity". Mr. Riley currently holds the position of Receiver in Lawrence Public Schools and has since that city's schools were put under state receivership. He recently resigned the Receiver's position and one wonders if that were serendipitous or by design.By many accounts, Ms. Infante-Green's interview was quite remarkable; she is a strong advocate of both bilingual and special education. As a parent of two bilingual children, one diagnosed with autism, she understands these two important issues intimately. While I disagree with some of her positions, she would have been a formidable advocate for bilingual students and for the differently-abled. To my thinking, the BESE members' failure to select her as Masachusetts' next Commissioner of Education is a lost opportunity: the opportunity to select the first woman to head the Commonwealth's Department of Elementary and Secondary Education and the first Latina to head Massachusetts' education.From each board members commentary, I think many of them supported Ms. Infante-Green's candidacy, but could not, in the end make that selection. It felt as if many of the eight who selected Mr. Riley did so based on a perception of "earning" the position after his tenure in Lawrence. It was safer. So what we seem to have here is a safe, unimaginative selection; hopefully I will be proven incorrect about that last part.Instead of breaking that glass ceiling, Massachusetts' Board of Elementary and Secondary Education chose the safe, known, local candidate. In doing so, have state policy-makers missed an opportunity for greatness? I believe so. Missed opportunity indeed. Last Tuesday, I was able to attend the Joint Committee on Education's hearing in Boston. I say "able" because, while I am sure the legislation before the Committee would have garnered interest and testimony from many active educators, they largely would not have been able to attend as the hearing took place the day after Labor Day, a school day. As a teacher retiree, I was not in my first (or fourth) day of a new school year and could attend, so I did.There were many proposed pieces of legislation under discussion last Tuesday; however, two bills, S.279 and H.304, aroused my curiosity and alarm. These two pieces of legislation appear to target teachers and students in gateway cities and, if you are a Massachusetts parent, teacher, or administrator and your student attends school in one of these districts, you should pay attention. Your voice in what happens in your local school is being threatened.Bill, S. 279 unnecessarily singles out and targets urban and gateway districts. How do I know this? Because the "opportunity" to become an innovation partnership zone is based on a the results of a single high-stakes test, the MCAS and consequently the assigned school level that stems from that test. To base the worth or value of a school - or a district - on how students perform on a single high-stakes exam is w.r.o.n.g. It is bad educational practice. No teacher would ever give a student a final mark based on one measure and the Commonwealth shouldn't be doing this with schools and school districts either.Those who favored moving H.304 and S.279 forward spoke frequently about the power of looking at students' (test) results and collaborating to determine school budget priorities, schedule/time allocations, and coordination of student needs with curriculum. My reaction to that is NO KIDDING. Why, why, why, do some in the Commonwealth feel that a piece of Legislation would make this a) any different from current practice, or b) necessary to mandate?Those in favor also spoke about the empowerment zone created in Springfield. The Springfield schools working in the empowerment zone are all middle schools and have done so for two years. Even James Peyser, Secretary of Education, had to admit the "data" on the success of these schools was rather green and not established. Others from this panel (two teachers and a principal) spoke about their experience meeting as teacher teams to think about what the students need.Sorry kids this is not a new concept or practice, nor is it one that requires a mandate from the Commonwealth. Lowell teachers, and I suspect teachers in most districts throughout Massachusetts, routinely meet to do this very same thing regularly. We call these collaborations PLCs (professional learning communities) or CPTs (common planning time). We do these things because a) we are there to figure out how to help students go from learning point A to B and b) we are professionals.Here's another thought: if a school is considered lower performing according to MCAS results, H.304 and S.279 would allow the Commissioner of Education (appointed, not elected) to begin the process of designating the schools for empowerment or innovation zone status. In the case of H.304, if the local teachers' union and the school committee cannot agree to concessions to the collective bargaining agreement, the Commissioner can just make the school a lower Level 4, and in effect, start the process of diluting local control anyway.Under S.279, the legislations proposes to "support" struggling schools through the creation of an innovation partnership zone. From what I can tell, the "partnership" is that the Commissioner of Education and DESE has a large stake in how the school is run. Schools are eligible to be in an innovation zone if their MCAS scores put them in Level 4 or Level 5 status. But - and this is key - in order to create an innovation zone, there needs to be at least 2 schools participating.Just to put that into local perspective, if Lowell has a Level 4 school (and it does) and the decision was made to create an innovation partnership zone for that school, the Commissioner of Education could pair that Level 4 school with another higher performing school - a Level 3, a Level 2 or a Level 1. So don't breathe easy if your school's MCAS results are great, you too could be part of this education magic show.When a school is "in the zone" (sorry Vygotsky fans, I couldn't resist that), an

Last Tuesday, I was able to attend the Joint Committee on Education's hearing in Boston. I say "able" because, while I am sure the legislation before the Committee would have garnered interest and testimony from many active educators, they largely would not have been able to attend as the hearing took place the day after Labor Day, a school day. As a teacher retiree, I was not in my first (or fourth) day of a new school year and could attend, so I did.There were many proposed pieces of legislation under discussion last Tuesday; however, two bills, S.279 and H.304, aroused my curiosity and alarm. These two pieces of legislation appear to target teachers and students in gateway cities and, if you are a Massachusetts parent, teacher, or administrator and your student attends school in one of these districts, you should pay attention. Your voice in what happens in your local school is being threatened.Bill, S. 279 unnecessarily singles out and targets urban and gateway districts. How do I know this? Because the "opportunity" to become an innovation partnership zone is based on a the results of a single high-stakes test, the MCAS and consequently the assigned school level that stems from that test. To base the worth or value of a school - or a district - on how students perform on a single high-stakes exam is w.r.o.n.g. It is bad educational practice. No teacher would ever give a student a final mark based on one measure and the Commonwealth shouldn't be doing this with schools and school districts either.Those who favored moving H.304 and S.279 forward spoke frequently about the power of looking at students' (test) results and collaborating to determine school budget priorities, schedule/time allocations, and coordination of student needs with curriculum. My reaction to that is NO KIDDING. Why, why, why, do some in the Commonwealth feel that a piece of Legislation would make this a) any different from current practice, or b) necessary to mandate?Those in favor also spoke about the empowerment zone created in Springfield. The Springfield schools working in the empowerment zone are all middle schools and have done so for two years. Even James Peyser, Secretary of Education, had to admit the "data" on the success of these schools was rather green and not established. Others from this panel (two teachers and a principal) spoke about their experience meeting as teacher teams to think about what the students need.Sorry kids this is not a new concept or practice, nor is it one that requires a mandate from the Commonwealth. Lowell teachers, and I suspect teachers in most districts throughout Massachusetts, routinely meet to do this very same thing regularly. We call these collaborations PLCs (professional learning communities) or CPTs (common planning time). We do these things because a) we are there to figure out how to help students go from learning point A to B and b) we are professionals.Here's another thought: if a school is considered lower performing according to MCAS results, H.304 and S.279 would allow the Commissioner of Education (appointed, not elected) to begin the process of designating the schools for empowerment or innovation zone status. In the case of H.304, if the local teachers' union and the school committee cannot agree to concessions to the collective bargaining agreement, the Commissioner can just make the school a lower Level 4, and in effect, start the process of diluting local control anyway.Under S.279, the legislations proposes to "support" struggling schools through the creation of an innovation partnership zone. From what I can tell, the "partnership" is that the Commissioner of Education and DESE has a large stake in how the school is run. Schools are eligible to be in an innovation zone if their MCAS scores put them in Level 4 or Level 5 status. But - and this is key - in order to create an innovation zone, there needs to be at least 2 schools participating.Just to put that into local perspective, if Lowell has a Level 4 school (and it does) and the decision was made to create an innovation partnership zone for that school, the Commissioner of Education could pair that Level 4 school with another higher performing school - a Level 3, a Level 2 or a Level 1. So don't breathe easy if your school's MCAS results are great, you too could be part of this education magic show.When a school is "in the zone" (sorry Vygotsky fans, I couldn't resist that), an  Board of Directors has autonomous control over personnel, budget, curriculum and hours. This unelected board with possibly no connection to the community could decide to do anything, including conversion of the public school to a charter school through a charter management company.Just for comparison, if a school is not in the zone, the

Board of Directors has autonomous control over personnel, budget, curriculum and hours. This unelected board with possibly no connection to the community could decide to do anything, including conversion of the public school to a charter school through a charter management company.Just for comparison, if a school is not in the zone, the